The problem 🛰

A rapidly increasing population of commercial low-Earth orbit (LEO) satellites is beginning to impact ground-based astronomy.

LEO satellites reflect sunlight and cause bright streaks in telescope images.

For an overview of the situation and its impacts to optical astronomy and beyond, see Lawrence et al. 2022.

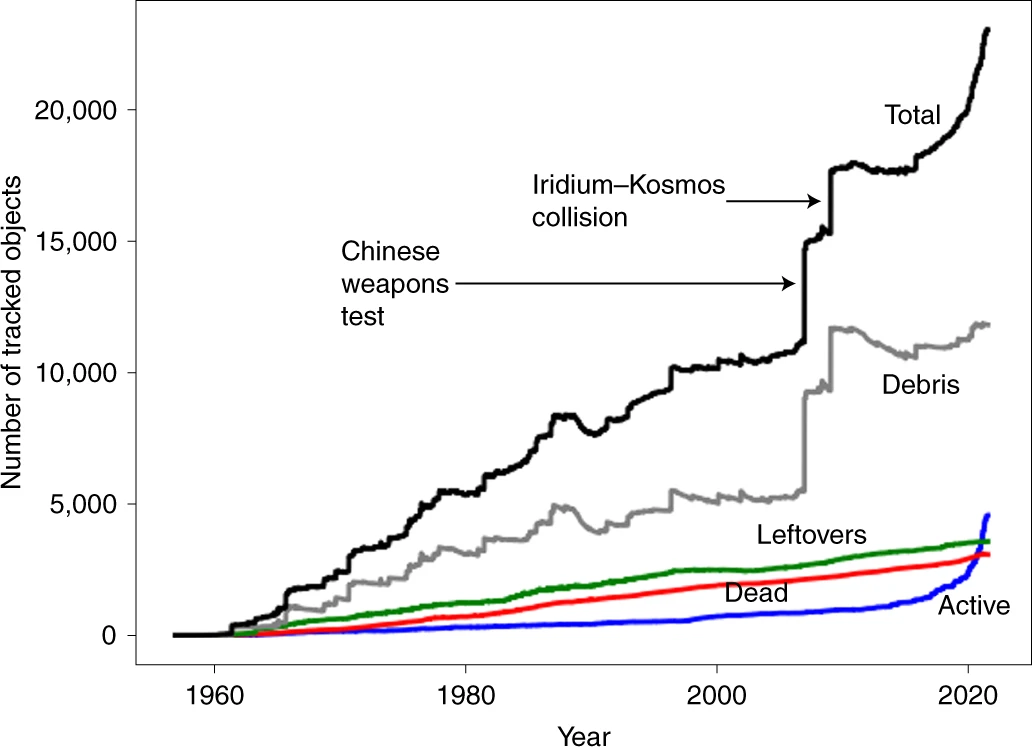

Growth of all tracked objects in orbital space over time.

“Dead” is derelict satellites, “Leftovers” is parts such as rocket stages, and “Debris” is smaller tracked material.

Commercial satellite constellations appear in the rapid “Active” line increase, and are much brighter than typical leftovers or debris.

Figure 1 from Lawrence et al. 2022.

While astronomers are in dialog with several satellite operator companies, and sincerely appreciate their efforts to darken their satellites, voluntary operator mitigations alone cannot solve the larger issue.

In addition, many image reduction pipelines are able to detect and mask (effectively ignore) most streaks from satellites, but it is impossible to erase them entirely.

Bright satellites are most numerous at twilight, and some science investigations like near-Earth asteroid searches are only possible at twilight.

Subtle effects like non-linear crosstalk and spatially correlated noise can further ruin specific science investigations.

And as much as astronomers would love more space telescopes, they are not a panacea—ground- and space-based telescopes are complementary.

Even if funds existed to design, build, and launch dozens of space telescopes beyond LEO, some groundbreaking science can only be accomplished from Earth-based facilties.

As the SATCON2 Executive Summary (2021) put it,

We are on the threshold of fundamentally changing a natural resource that since our earliest ancestors has been a source of wonder, storytelling, discovery, and understanding of ourselves and our origins. We transform that at our peril.Promptly addressing this urgent issue is crucial to maximize the scientific return of ground-based astronomy worldwide.

Our approach 🤩

To minimize some impacts on astronomy, Trailblazer aims to enable quantitative studies of streaks from satellites in images over time.

Trailblazer collects and shares recent (c. 2020–present) telescope images in the FITS file format known to contain one or more satellite streaks.

To better disseminate the impact of satellite streaks on astronomy, each uploaded image also appears in a gallery. Trailblazer will always be public, free, and open source, and aims to enable astronomers and any other stakeholders to collaborate on mitigating the impact of satellite streaks.

How to contribute 🔭

There are two main Trailblazer user roles:

- Astronomers who intentionally or unintentionally observe satellites in their images and wish to salvage some value from them by contributing to Trailblazer, and

- Groups seeking to characterize the extent of the satellite streak problem who need access to a dataset to better quantify and mitigate impacts as the satellite population changes.

Please contact us directly if…

- You have more than about 100 images you'd like to upload

- You have experience with Django and Python and would like to volunteer as a web developer

The team 👨💻

Trailblazer was conceived and initially developed by Meredith Rawls and Dino Bektešević.

Other contributing team members include:

- Siegfried Eggl, University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign (UIUC)

- Michele Bannister, University of Canterbury New Zealand (UCNZ)

- Jasmine Watt, UW astronomy undergraduate student

- Weifeng Li, UW CSE undergraduate student

- Abas Hersi, UW CSE undergraduate student

- Anthony Rihani, UIUC aerospace undergraduate student

- Erin Howard, WWU physics/astronomy undergraduate student

- Joe Kent, UCNZ undergraduate student